From March to June 2008, Nicholas Hirshon wrote a nine-part series for the New York Daily News named “History in Peril,” highlighting historic buildings that were in danger of demolition because the city had never declared them official landmarks.

From March to June 2008, Nicholas Hirshon wrote a nine-part series for the New York Daily News named “History in Peril,” highlighting historic buildings that were in danger of demolition because the city had never declared them official landmarks.

First Installment: Landmarking on the Agenda

Published March 18, 2008

Queens, the city’s largest borough, historically has attracted an eclectic mix of iconic artists, athletes and thinkers.

Queens, the city’s largest borough, historically has attracted an eclectic mix of iconic artists, athletes and thinkers.

But you wouldn’t know that by counting its landmarks.

That may change in the wake of a city-commissioned survey of 12,495 buildings in Queens, which has the fewest stand-alone landmarks – 69 – of any borough, just a tenth of Manhattan’s.

That survey could be vital in saving the borough’s heritage at a time when a building boom is sweeping across Queens.

“It gives us an opportunity to focus on more designations where they’re warranted, and also to get ahead of the curve on any buildings that may be endangered,” said Landmarks Commission Chairman Robert Tierney.

Queens preservationists have been critical of the commission, but remain cautiously optimistic about the survey.

However, they fear some noteworthy, at-risk sites won’t win designations, given the commission’s record of favoring architecture over historical significance.

With that in mind, Queens News is kicking off a “History in Peril” series – offering profiles of unlandmarked sites.

To be declared a city landmark, according to the guidelines, a structure must be at least 30 years old and possess “a special character or special historical or aesthetic interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the city, state or nation.”

Once a landmark is designated by the commission and approved by the City Council, the building owner needs the commission’s consent to change the facade or significant architectural features.

Income-eligible owners can also apply for upkeep grants.

With such protections, landmark designation is the surest way to maintain a historic gem, preservationists contend.

“Areas throughout the city feel the development pressure,” said Peg Breen, president of the New York Landmarks Conservancy. “It’s crucial to get ahead of the game a little bit.”

Queens Historical Society President Jim Driscoll said the survey will lead to designations – but “maybe not the ones we want or as many as we want.”

He criticized the mayoral-appointed, 11-member commission – three architects, a historian, a Realtor, a planner or landscape artist and reps from each borough – for ignoring Queens.

Nancy Cataldi, president of the Richmond Hill Historical Society, said the agency hasn’t been eager to consider local sites. “It’s very frustrating,” she said. “They’re not listening.”

Others gripe the commission relies too much on the City Council – perhaps by necessity, since the Council gets final say on designations.

In 2005, when preservationist Michael Perlman pushed for designation of the Art Deco-style Trylon Theater in Forest Hills, Tierney sought approval from local Councilwoman Melinda Katz.

But Katz didn’t take a position on the movie house, and the commission shot the effort down. Crews gutted and renovated the Trylon into a Bukharian Jewish center.

Recent years, however, have brought promise.

Since Mayor Bloomberg took office in 2002, the commission has designated 661 Queens structures, including those in historic districts. In February, it landmarked a Corona synagogue and former Jamaica bank.

“The idea that some say we’re either neglecting Queens or something, Queens is not getting the attention the rest of the city gets, is not borne out by these facts,” Tierney said.

Moving forward, the best way to get a Queens site landmarked is to highlight its role in the community, said Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council.

“Buildings don’t exist in a vacuum,” he said.

SIDEBAR: It’s a Pity! They Could Have Been Saved

Helen Keller made a home in Queens. So did pioneering photojournalist Jacob Riis. Legendary boxers and wrestlers even grappled at a fabled arena on the borough’s main thoroughfare.

Helen Keller made a home in Queens. So did pioneering photojournalist Jacob Riis. Legendary boxers and wrestlers even grappled at a fabled arena on the borough’s main thoroughfare.

But you can’t visit these historic structures: None had been landmarked and all were destroyed.

The Forest Hills house where the blind-and-deaf Keller spent two decades – at 71-11 112th St. – was demolished in 1962 to make way for a synagogue, said historian Jeff Gottlieb.

Three years later, the city created its Landmarks Preservation Commission. Had the home been landmarked, tourists might still be visiting what Keller wrote was an “odd-looking house” with “so many angles and peaks and queer windows, we call it our ‘castle on the marsh.’”

“This is her legacy and it’s just very sad, but hopefully we can learn and not do silly stuff like this again,” said Helen Selsdon, archivist for the American Foundation for the Blind.

And yet, even on the commission’s watch, the Richmond Hill home where Riis resided for 27 years and wrote his classic “How the Other Half Lives” was razed in 1973 – after being named to the National Register of Historic Places, an honor with no protection.

Experts said 84-39 120th St. offered a clue on an interesting tidbit of the muckraker’s career.

“The guy who was most identified with depicting the grim realities of tenement life and the immigrant poor didn’t even live in Manhattan,” said author Daniel Czitrom, who co-wrote “Rediscovering Jacob Riis.”

But Landmarks officials never considered Riis’ home, a spokeswoman said, because they didn’t receive public requests about it.

They also never looked into the storied Sunnyside Garden, a red-brick arena at 44-16 Queens Blvd. where boxing matches often devolved into race wars.

A sellout crowd of 2,000 turned violent after a March 31, 1967, bout between “Irish” Bobby Cassidy and Puerto Rican pugilist Carmelo Hernandez.

“I won, and the bottles started coming,” said Cassidy, 63, who fought in a record 26 main events at Sunnyside. “I hid underneath the ring. I couldn’t get back to the dressing room.”

Sunnyside also hosted wrestling stars like Bruno Sammartino and gargantuan hillbilly Haystacks Calhoun, who wore overalls and a horseshoe necklace.

Long after the 1977 demise of Sunnyside Garden, however, the bulldozers still haven’t let up on historic sites.

Scaffolding still stands where a developer leveled a Forest Hills mansion at 68-12 110th St. once owned by jazz singer Al Jolson.

“This was one of his myriad investments,” said Ed Greenbaum, a historian with the International Al Jolson Society. “It’s one of the reasons he died wealthy and did not get creamed by the Great Depression.”

SIDEBAR: Places in Boro’s Heart

We get no respect! With Queens lagging behind the other boroughs in the number of city landmarks designations, preservationists identified these five structures among the most worth saving.

We get no respect! With Queens lagging behind the other boroughs in the number of city landmarks designations, preservationists identified these five structures among the most worth saving.

1. New York State Pavilion

Flushing Meadows-Corona Park

Constructed for the 1964-65 World’s Fair, the pavilion features three towers and the “Tent of Tomorrow” rotunda, with a terrazzo New York State map and cable suspension roof. The towers exhibit cracks, and the cables appear bare without the multicolored panels they once held in place. The city has commissioned a $200,000 study of the roof and is overseeing restoration of some map tiles.

2. James Brown Home

175-19 Linden Blvd., Addisleigh Park

Cootie Williams, a trumpeter in the Duke Ellington Orchestra, sold the three-story, Tudor-style home to the thirtysomething Brown, who resided there from 1963 to 1968. Music greats Count Basie and Illinois Jacquet lived within blocks, but neighbors focused on the exuberant, up-and-coming “Godfather of Soul” – who erected a high fence to fend off sightseers, said Marc Miller, who helped create the Queens Jazz Trail map in 1998. The fence, reportedly emblazoned with “JB” monograms, is now gone. The house

is currently on the market.

3. Nancy Reagan Childhood Home

149-40 Roosevelt Ave., Flushing

The former First Lady’s first home was an unassuming two-story house – now with green aluminum siding. Edith and Kenneth Seymour Robbins lived there when their destined-for-fame daughter, Anne Frances, was born in 1921. The girl who grew up to become Nancy Reagan spent two years in Flushing before moving in with relatives in Maryland, according to a 1991 unauthorized biography by Kitty Kelley.

4. Pearl-Bullard-Eccles-Kabriski Mansion

147-38 Ash Ave., Flushing

Built as a summer retreat in the 1840s, this white wood mansion remains the oldest freestanding “cottage” left in Flushing, said historic preservation consultant Paul Graziano. After original owner Charles Pearl died in 1884, his daughter sold the home to the Bullard family – whose son, Roger Harrington Bullard, became a famous architect and may have renovated the mansion’s complex porches. Later owners were the Rev. George Eccles of St. John’s Episcopal Church and contractor Matthew Kabriski.

5. West Side Tennis Stadium

69th Ave. and Dartmouth St., Forest Hills

Home to the U.S. Open from 1924 to 1977, the 14,000-seat, horseshoe-shaped arena was where Don Budge completed the first-ever tennis Grand Slam in 1938, said Eugenia Frangos, an archivist for the West Side Tennis Club. Other notables to grace the court include Althea Gibson, Arthur Ashe, Jimmy Connors, John McEnroe and Billie Jean King. The concrete venue also hosted the Beatles, the Doors, the Monkees, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and Frank Sinatra.

Queens News will profile several potential landmarks in coming weeks in addition to these. Coming Next Week: A posh Queens home where one of the world’s most famous civil rights advocates wooed his future wife is for sale. Will it be destroyed? Read more on March 25 in Queens News.

Second Installment: Injustice to Du Bois Home

Published March 25, 2008

Dressed in a tuxedo, civil-rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois married an activist nearly three decades his junior on Feb. 27, 1951, in a posh house in southeast Queens.

Dressed in a tuxedo, civil-rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois married an activist nearly three decades his junior on Feb. 27, 1951, in a posh house in southeast Queens.

The exterior of the Addisleigh Park home where Du Bois, 83, wed Shirley Graham, 54, is remarkably unchanged from what the couple’s friends would recall. But it also remains unlandmarked at a time when a building boom is sweeping across the borough.

“It’s a site that needs some recognition by the Landmarks Commission,” said NAACP Chairman Julian Bond, heaping praise upon Du Bois, the organization’s co-founder.

“They certainly ought to take note of it,” Bond added. “I’d advise them at least that a plaque be placed nearby.”

Jane Cowan, a research consultant for the Historic Districts Council, said she was combing through city finance records a few months ago when she found a deed connecting Graham Du Bois to 173-19 113th Ave.

Queens News matched the address to a photo taken of the home in the late 1940s. The photo was given by Graham Du Bois’ son, David Du Bois, to author Gerald Horne as he researched his 2000 book “Race Woman: The Lives of Shirley Graham Du Bois.”

The home’s current owner, Helen Baldwin, said her family moved there in the 1970s and has made only minor changes, like fixing the roof and adding a layer of stucco.

Baldwin said she wants to stay in the house, but developers keep calling unprompted to ask if she’s selling it. She also said she wouldn’t alter its look, adding, “I like it the way it is.”

Even if it’s sold, high-rise developers need not apply. Recent zoning changes restrict the area to one-family homes, said Yvonne Reddick, district manager of Community Board 12.

But only landmarking would prevent someone from knocking down the historic house.

“It deserves landmark status,” said Horne, an African-American studies professor at the University of Houston. “It’s not only redolent with black American history, but U.S. history.”

Guidelines require landmarks to be at least 30 years old and possess a “special historical or aesthetic interest or value” to the “heritage or cultural characteristics of the city, state or nation.”

The commission declined to provide its recent survey of 12,495 Queens structures to Queens News, so it’s unclear if the home is under consideration.

Historian Jeff Gottlieb said the commission is more likely to designate it if the state and national historic registers do so first.

Graham, a noted playwright and biographer, moved into the house in 1947, shortly after locals canceled a covenant that forbade blacks from living on the block, Cowan said.

At the 1951 wedding, guests dined on toasted sandwiches, canapes, ice cream and sparkling punch, as a news reel crew captured every move, David Du Bois told Horne.

In a letter to a friend, Graham Du Bois wrote she would sell the home because “it’s too far out from the center of our activities – takes too long to get back and forth,” specifically to and from Harlem.

The powerful pair soon moved to Brooklyn. He died in 1963; she died in 1977.

SIDEBAR: Movie Palace Shuts

From Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, through the advents of the TV and VCR, the Ridgewood Theatre never stopped showing films – until its streak ended this month, eliciting concern about the unlandmarked site’s future.

From Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, through the advents of the TV and VCR, the Ridgewood Theatre never stopped showing films – until its streak ended this month, eliciting concern about the unlandmarked site’s future.

For the first time since its opening on Dec. 23, 1916, the ornate movie house was shuttered, after its March 9 screenings, ending an almost century-long run that made it one of the nation’s oldest continuously operated theaters.

The Ridgewood’s new owner, real estate agent Tony Montalbano, said there’s a “90%” chance the five-screen site will show movies again – though its two ground-floor theaters may be converted into a clothing shop.

Fearing significant exterior changes, some theater experts are calling on the city Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate the Ridgewood, making it illegal to alter the facade without commission approval.

“People don’t realize what the theater is,” said Orlando Lopes, the New York director of the Theatre Historical Society of America. “It never missed a day.”

Despite being multiplexed in 1980 – from one screen to five – the theater retains its original upper facade, along with a terrazzo floor and ornamental dome, said Warren Harris, a biographer of film stars.

Montalbano, who said the Ridgewood “does mean a lot to me,” because he went there as a kid, vowed to spend $1.5 million to spruce it up – but wouldn’t say if he’d support landmarking.

It is unknown whether the Ridgewood was included on the commission’s recent survey of 12,495 Queens buildings. Landmarks officials refused to provide the survey to Queens News.

The theater’s long history began with glorious predictions in the Ridgewood Times on Dec. 22, 1916: “No more hurry and scurry on the part of our people to get to some downtown show . . . Ridgewood will be able to see the highest class vaudeville right in its own section.”

The next day, William Fox opened the Ridgewood – with some 2,000 seats – with tickets for a film and six vaudeville acts ranging from 10 to 25 cents.

Fox went bankrupt and lost the theater in the Great Depression. It later joined a chain that became United Artists, before being purchased in the 1980s by the family that sold it to Montalbano.

Filmmaker Edward Summer, who is pushing to create a New York State Movie Theater Corridor with a guidebook and commemorative plaques, has vowed to include the Ridgewood.

Montalbano also could buy a $290 yearly membership from the League of Historic American Theatres, which connects moviehouse owners to rehabilitation experts, said the league’s Executive Director, Fran Holden.

Third Installment: On the Road to Saving Two Kerouac Sites

Published April 1, 2008

Poring over books and maps in his mom’s Ozone Park apartment, Jack Kerouac planned the most famous road trip in literary history – and embarked on it in 1947.

Poring over books and maps in his mom’s Ozone Park apartment, Jack Kerouac planned the most famous road trip in literary history – and embarked on it in 1947.

But neither the walk-up where Kerouac plotted his cross-country exploits, nor a South Richmond Hill home where he worked on the classic novel “On the Road,” are protected with city landmark status.

“Without question, they should be city landmarks. No book has captured the public imagination like ‘On the Road,’ ” said Douglas Brinkley, a CBS News history analyst and Kerouac scholar.

To aid a landmark push, Indianapolis Colts owner Jim Irsay told Queens News he would consider loaning the original 120-foot “On the Road” manuscript – a unique, continuous scroll that he purchased for $2.4 million in 2001 – for display at the borough sites.

“You always consider putting it in a place where it’s conceived,” Irsay said. “The man has left the building, so to speak, but, at the same time, these places that are preserved, they mean a lot.”

It’s unknown whether the city Landmarks Preservation Commission has Kerouac’s homes on its recent survey of 12,495 Queens structures. The commission has repeatedly declined to provide the survey to Queens News, fearing its release would alert developers to the sites before they can be protected.

Writer Patrick Fenton helped put a plaque outside the apartment in 1996 – just after the Lindenwood Volunteer Ambulance Corps moved in and gutted the space, without realizing its link to Kerouac.

“The organization would have tried to save more of the history if we knew,” said Corps Chief Chris DeLuca. Still, the walls and door frames are original. “There’s a lot of history up there,” Fenton said.

In the early 1950s, Kerouac’s mom moved to 94-21 134th St. in South Richmond Hill, where the author lived on and off over five years, and wrote “Maggie Cassidy,” Fenton said.

The home’s current owner, Lester Holt, arrived in 1984 and oversaw a major renovation. When told landmarking would require him to consult the commission before making more changes, he said, “I ain’t interested in all of that.”

But the next spot where Kerouac lived – a cottage in Orlando, Fla. – offers inspiration to preservationists. A grassroots effort saved it from destruction.

Kerouac was living there in 1957, when the publication of “On the Road” made him the voice of the Beat Generation. Forty years later, despite the home’s history, it appeared destined for demolition.

Enter Florida book dealer Marty Cummins, who helped raise $10,000 for a down payment on the home in 1997. But he was short $100,000 to close the deal – until corporate titan Jeffrey Cole pledged the funds.

Now, the house is provided rent-free to writers for three-month stays. Cummins predicted a similar result in Queens.

“The key is finding an advocate or an angel backer who will step up to the plate,” he said.

That could be Cole, the former chairman of Cole National, who promised to look into Kerouac’s Queens homes. “It’s always a good idea if some of these artists’ and writers’ places can be saved,” Cole said.

SIDEBAR: Queensmark Committee Mulls Comeback

A decade ago, fearing Queens had become “Landmarks’ stepchild and the developer’s paradise,” historian Stanley Cogan helped create the Queensmark – a way of recognizing structures that weren’t landmarks.

A decade ago, fearing Queens had become “Landmarks’ stepchild and the developer’s paradise,” historian Stanley Cogan helped create the Queensmark – a way of recognizing structures that weren’t landmarks.

By the time the program went inactive a few years ago – a victim of Cogan falling ill – some 100 plaques had sprouted in places like Richmond Hill, Jackson Heights and Whitestone.

Now, amid a building boom, the Queensmarks committee is mulling a reunion. But others fear the honors won’t win landmark designations – and may instead alert developers to historic places they’ll demolish before they can be protected.

“Signage is a perfectly fine thing, and it can be an effective public education tool, but it doesn’t save buildings,” said Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council.

Still, four former committee members told Queens News they want to reactivate Queensmarks – last awarded in 2003 – with Jim Driscoll, the historical society’s new president, acting as committee chairman.

“If you telegraph your plans, developers will just move as fast as they can. But in the case of the Queensmarks, no,” Driscoll said, noting the honors often go to private homes, which the owners don’t want to sell.

For the first wave of Queensmarks in 1996, Cogan organized a six-member panel to find noteworthy sites, contact owners and ask them to affix a plaque provided by the society to the exterior.

Committee members would walk through neighborhoods and snap hundreds of photos. They debated each site’s merits based on its architecture, history and importance to the area.

“It was not our job to be ivory-tower types. It was our job to understand the community,” said Jeffrey Saunders, who specialized in pre-World War II architecture.

Architect Allan Smith recalled putting the photos into piles of definitelys, maybes and maybe-nots.

“Sometimes you’d take a picture of something, and when you went back for a final look, it may not be there,” he said of the task’s urgency.

Next, they had to convince owners to put up the plaques.

“Some of them were afraid that this will lead to landmarking and ‘I don’t want that,’ ” said architect Ivan Mrakovcic.

Their efforts put some hidden gems on the path to protection. A 1999 Queensmarks honoree, Tifereth Israel synagogue in Corona, was designated a city landmark this February.

But the Landmarks Preservation Commission said it weighs all public requests, including Queensmarks, on an equal scale.

“It would be a factor, but it’s not the factor,” said spokeswoman Lisi de Bourbon. “The factors for us are whether the building is culturally, architecturally and historically distinctive.”

Fourth Installment: Jackie Robinson’s House Not Safe

Published April 8, 2008

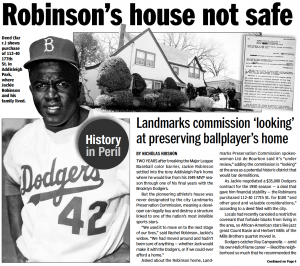

Two years after breaking the Major League Baseball color barrier, Jackie Robinson settled into the tony Addisleigh Park home where he would live from his 1949 MVP season through one of his final years with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Two years after breaking the Major League Baseball color barrier, Jackie Robinson settled into the tony Addisleigh Park home where he would live from his 1949 MVP season through one of his final years with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

But the pioneering athlete’s house was never designated by the city Landmarks Preservation Commission, meaning a developer can legally buy and destroy a structure linked to one of the nation’s most indelible sports stars.

“We used it to move on to the next stage of our lives,” said Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow. “We had moved around and hadn’t been sure of anything – whether Jack would make it with the Dodgers, or if we could ever afford a home.”

Asked about the Robinson home, Landmarks Preservation Commission spokeswoman Lisi de Bourbon said it’s “under review,” adding the commission is “looking” at the area as a potential historic district that would bar demolitions.

As Jackie negotiated a $35,000 Dodgers contract for the 1950 season – a deal that gave him financial stability – the Robinsons purchased 112-40 177th St. for $100 “and other good and valuable considerations,” according to a deed filed with the city.

Locals had recently canceled a restrictive covenant that forbade blacks from living in the area, so African-American stars like jazz great Count Basie and Herbert Mills of the Mills Brothers quartet moved in.

Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella – amid his own Hall of Fame career – liked the neighborhood so much that he recommended the Robinsons buy a house there, Rachel Robinson said.

While Jackie Robinson remains a national icon, the city is more likely to landmark his home and those nearby because of his role in integrating the area, said Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council.

Jackie and Rachel hoped for a peaceful life in the house with their kids Jackie Jr., born in 1946, and Sharon (1950) and David (1952). But sightseers destroyed the tranquility.

“Well-meaning people constantly harassed us,” Jackie Robinson wrote in his 1972 autobiography, “I Never Had It Made.” “They would pull up in their cars, walk boldly into our front yard and start taking pictures.”

He recalled Rachel being thrust into a lose-lose situation: either accept the nuisance or insist on privacy and risk being labeled an ungrateful stuck-up. But Rachel had other concerns.

“When Jack started getting hate mail, we worried about the children and their playing outside,” she said, adding they eventually decided not to let the racist words affect them.

With the Robinson family outgrowing the home, especially after David’s birth in 1952, they sold it in 1955 to John and Gugurtha Dudley, acquaintances of the Robinsons’ real estate broker. The Dudleys resided there until 1985.

“It was a very big deal that we bought their house, because we were small people,” said Gugurtha Dudley, 87, now of Atlanta, Ga. “We weren’t high on the totem pole with the Robinsons.”

Jackie and his family moved to North Stamford, Conn. He died at age 53 in 1972.

SIDEBAR: Rally for Kerouac Homes

Emboldened by a Queens News profile on two unlandmarked Jack Kerouac homes, fans of the beat writer are planning a July get-together to discuss preserving his legacy.

Writer Patrick Fenton said he will take book dealer Marty Cummins and corporate bigwig Jeffrey Cole – who saved a Kerouac home in Orlando, Fla., from demolition – on a tour past Kerouac’s Ozone Park apartment and South Richmond Hill house.

Neither was included in the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s recent survey of 12,495 Queens structures, and the city never received requests to evaluate them, said commission spokeswoman Lisi de Bourbon.

“There are a lot of very important people who lived in New York City at one point or another,” she said, noting not every location associated with a famous person can be landmarked.

“And we have very few cultural landmarks in the city,” de Bourbon said of the difference between architectural gems and those with only historical weight.

A plan to put the original “On the Road” manuscript – a 120-foot scroll – on display at the homes would be “unlikely” to influence the commission, de Bourbon said.

SIDEBAR: Sites Tied to Ballplayers Threatened

A Queens building boom is threatening the borough’s link to unforgettable ballplayers who lived and played here on paths to Hall of Fame careers, preservationists fear.

A Queens building boom is threatening the borough’s link to unforgettable ballplayers who lived and played here on paths to Hall of Fame careers, preservationists fear.

With Shea Stadium opening its final season this week – and destined for demolition at the end of 47 seasons of Mets baseball – the area’s ties to bygone superstars will remain largely in unlandmarked homes, as developers wait on deck.

“Preserving baseball history is absolutely essential,” said Roberta Newman, a historian of the sport who teaches at New York University. “It’s got deep roots in American culture.”

Months before Jackie Robinson moved into Addisleigh Park in 1949, his Brooklyn Dodgers teammate Roy Campanella bought a home at 114-10 179th St., after finishing his first Major League catching campaign. He stayed until 1956.

Dodgers historian Joseph Dorinson urged landmark status for the three-time MVP’s house. “If Jackie was the heart of the Dodgers’ resurgence in the late ’40s and early 1950s, Campanella was the soul,” Dorinson said.

But they weren’t the last greats to visit Queens. In the 1960s, Willie Mays often visited 108-01 Ditmars Blvd. in East Elmhurst, where his ex-wife Marghuerite lived with their son Michael, said biographer Mary Kay Linge.

Another agile centerfielder, the Mets’ Tommie Agee, lived near 29th Ave. and Butler St. in East Elmhurst. The two-time Gold Glover is best remembered for two spectacular catches in Game 3 of the 1969 World Series.

“He (Agee) was close to being what we call a five-tool player,” said 1969 Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson, now a co-owner of the Long Island Ducks independent baseball club. “We certainly couldn’t win without him.”

Agee’s heroics occurred at Shea, which will be dismantled two to three weeks after the Mets finish the 2008 season.

In 1997, when the Braves demolished Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, workers marked its foul lines and bases in the new stadium’s parking lot.

Will the Mets follow suit?

“All being discussed; nothing yet finalized,” said a team spokesman.

Other pieces of the sport’s past are already gone.

To build the U.S. Naval Hospital at Linden Blvd. and 179th St. in 1950, crews destroyed the historic St. Albans Golf Club, where Yankees icon Babe Ruth played regularly from the late 1920s through the 1940s.

The Veterans Administration took over the land in 1974 for a medical center, said agency spokesman Raymond Aalbue. But Ruth’s ties to Queens live on at the New Hampshire home of his 91-year-old daughter, Julia. A silver trophy the Babe won at St. Albans is on display there.

Fifth Installment: A Witness to World Events

Published April 15, 2008

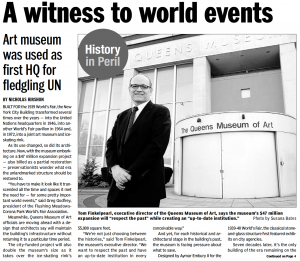

Built for the 1939 World’s Fair, the New York City Building transformed several times over the years – into the United Nations headquarters in 1946, into another World’s Fair pavilion in 1964 and, in 1972, into a joint art museum and ice-skating rink.

Built for the 1939 World’s Fair, the New York City Building transformed several times over the years – into the United Nations headquarters in 1946, into another World’s Fair pavilion in 1964 and, in 1972, into a joint art museum and ice-skating rink.

As its use changed, so did its architecture. Now, with the museum embarking on a $47 million expansion project – also billed as a partial restoration – preservationists wonder what era the unlandmarked structure should be restored to.

“You have to make it look like it transcended all the time and spaces it met the need for – for some pretty important world events,” said Greg Godfrey, president of the Flushing Meadows-Corona Park World’s Fair Association.

Meanwhile, Queens Museum of Art officials are moving ahead with a design that architects say will maintain the building’s infrastructure without returning it to a particular time period.

The city-funded project will also double the museum’s size as it takes over the ice-skating rink’s 55,000 square feet.

“We’re not just choosing between the histories,” said Tom Finkelpearl, the museum’s executive director. “We want to respect the past and have an up-to-date institution in every conceivable way.”

And yet, for each historical and architectural stage in the building’s past, the museum is facing pressure about what to save.

Designed by Aymar Embury II for the 1939-40 World’s Fair, the classical stone-and-glass structure first featured exhibits on city agencies.

Seven decades later, it’s the only building of the era remaining on the fairgrounds – site of a deadly 1940 terrorist act.

Detectives Joseph Lynch and Ferdinand Socha were killed on July 4, 1940, when a bomb they were trying to defuse exploded.

Lynch’s daughter, Easter Miles, called the New York City Building the last standing tribute to her fallen dad.

“I would vote for it to be a landmark,” she said.

In the next chapter in the building’s history, the interior was radically gutted to create a home for the United Nations General Assembly in 1946. A vote that created the state of Israel occurred in Flushing Meadows on Nov. 29, 1947.

“It was one of the early UN buildings. There aren’t that many,” said Stanley Meisler, author of “United Nations: The First Fifty Years.”

As part of the upcoming expansion, scheduled for completion in 2010, the museum wants to put plaques at UN-specific spots in the building, including where President Harry Truman gave an important 1946 speech on isolationism, Finkelpearl said.

Plans also call for partial restoration of a colonnade, on the museum’s Unisphere side, that was intact at the 1939-40 fair and during the building’s United Nations years, Finkelpearl said.

For the 1964-65 World’s Fair, the structure again became a city pavilion – featuring a cross-section of cable from the Verrazano Bridge and a detailed panorama of New York City, said Bill Cotter, author of books about the fair.

During the expansion, the museum will remove bris soleil shading panels – attached before the 1964-65 fair – from its Grand Central Parkway facade, Finkelpearl said.

SIDEBAR: ’30s Theater Now Part of Film History

A Great Depression-era movie theater in Jackson Heights was recently torn down after a 70-year history that began with showings of star-studded classics and ended with a long run of X-rated flicks.

A Great Depression-era movie theater in Jackson Heights was recently torn down after a 70-year history that began with showings of star-studded classics and ended with a long run of X-rated flicks.

The Polk Theatre, at 37th Ave. and 93rd St., featured framework from its original 1938 marquee and numerous Art Deco-style elements before its demolition in February, preservationists said.

“It had the kind of style and character that you don’t have today – and you’ll never have again,” said architectural historian Barry Lewis. “It’s sad that this was torn down.”

Architect Charles Sandblom designed the 599-seat movie house. A 1960s switch from feature films to adult movies helped business but led to a period when the theater wasn’t maintained, said Warren Harris, a biographer of film stars.

While some preservationists seemed indifferent about the Polk’s demise, pointing out it was never a movie palace, others disagreed.

“Theaters, like churches, are anchors for a community,” said filmmaker Edward Summer, who is leading a statewide effort to put plaques on historic movie theaters. “When you lose that anchor, the community begins to drift.”

The Polk’s longtime owner, Harold Gussin, said he operated the theater from 1961 until he sold it in 2006. His wife, Eleanor, griped that business was undercut by DVD sales.

“I used to work night and day,” said Gussin, 82, who lives in Valley Stream, L.I. “Rain, shine, snow, I was there.”

The new owner, Henry Zheng, said he wasn’t yet sure what he’d build at the site. But Eleanor Gussin said she heard Zheng wants to put up a mixed-use building with apartments and stores.

Lewis, meanwhile, found the Polk’s descent in line with what’s happened to other old theaters. “Unless they find new uses for them, the market says they’re ready for the garbage,” he said.

SIDEBAR: HOFer Home on Radar

City officials are eying the home of baseball Hall of Famer Roy Campanella – featured in last week’s Queens News – as part of a possible Addisleigh Park historic district.

The designation would bar the demolition of 483 buildings in the tony Queens neighborhood, once home to many famed African-American music greats, said Lisi de Bourbon, a spokeswoman for the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Asked if the commission would judge the area based on its history or architecture, de Bourbon said, “When you look at a historic district, there has to be a coherent streetscape and a distinct sense of place.”

She declined to predict if the commission would approve the district, saying only, “It’s still under review.”

Sixth Installment: A Malcolm X Memorial?

Published April 22, 2008

Asleep with his wife and four daughters in their modest East Elmhurst home, Malcolm X jumped out of bed and out the door at 2:45 a.m. on Valentine’s Day 1965 as Molotov cocktails crashed through the windows and exploded.

Asleep with his wife and four daughters in their modest East Elmhurst home, Malcolm X jumped out of bed and out the door at 2:45 a.m. on Valentine’s Day 1965 as Molotov cocktails crashed through the windows and exploded.

Unscathed but shaken, the civil rights leader moved out days later – and was assassinated on Feb. 21. But while the house served as Malcolm X’s sanctuary in his turbulent last years, the city has never protected it with landmark status.

“There’s a lot of history there, and there’s no reason to lose it,” said Ilyasah Shabazz, one of the black activist’s daughters, who was 2 years old when he died. The city would be “smart to preserve it,” she said.

A proposal by City Councilman Hiram Monserrate (D-East Elmhurst) – reportedly supported by the home’s residents – would place a Malcolm X memorial near the humble green house.

Monserrate, who didn’t return calls seeking comment, has previously said he’d like the Queens of Museum of Art to turn the Malcolm X house into a museum.

But Tom Finkelpearl, the museum’s executive director, said his budget wouldn’t allow for that plan. “We just can’t do it now,” he said. “That doesn’t mean in 10 years we can’t consider doing it.”

Malcolm X rose to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s for his controversial, militant civil rights stances as a member of the Nation of Islam, a powerful black Muslim organization.

Some believe city officials ignored his Queens home because of his ferocious image.

“He gets the short end of the stick because of the way he’s been portrayed in history as being militant and advocating violence,” said Kira Duke, education coordinator at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

In July 1960, at the height of Malcolm X’s run with the Nation of Islam, he and his family moved into the small Queens brick home, which was owned by the organization.

Ilyasah Shabazz – then an infant – said she often waited for her dad to come home so they could play and eat cookies her mom, Betty, made for them.

But Malcolm X’s changing ideology and controversial remarks on the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy led to a rift with the Muslim group’s leader, Elijah Muhammad.

The Nation of Islam soon threatened to evict the family. Malcolm X initially refused to leave, giving way only after the 1965 firebombing.

SIDEBAR: Dem Beep Hopefuls Eye Black History Trail

Leading candidates for Queens borough president said they support the idea of a black history trail, with sites from the Queens News’ History in Peril series, including the former homes of Malcolm X, Jackie Robinson and James Brown.

Leading candidates for Queens borough president said they support the idea of a black history trail, with sites from the Queens News’ History in Peril series, including the former homes of Malcolm X, Jackie Robinson and James Brown.

Proponents of the plan – seeking a funding boost from the borough’s next top official – reveled in backing from the four Democratic contenders: Leroy Comrie, Audrey Pheffer, Helen Sears and Peter Vallone Jr.

“They must feel it has merit,” said Clyde Bullard, who has run the Queens Jazz Trail tour for 10 years and is pitching the black history trail idea to his bosses at Flushing Town Hall, the home of the Flushing Council on Culture and the Arts.

“The borough president could reach in and hand them the funds to do it,” said Marc Miller, who created the map that formed the basis of the Jazz Trail. “It’s probably the easiest source.”

The four Democratic contenders vowed to consider a trail centered on sites like the Addisleigh Park home where W.E.B. Du Bois got married in 1951 and the Forest Hills tennis stadium where Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson played.

“That would be wonderful,” said Pheffer, an assemblywoman who represents southern Queens. “Queens is a borough of neighborhoods and diversity, and any time we can bring it out, it makes everyone know Queens is so special.”

Sears, a city councilwoman in northern Queens, added she’d “certainly support the idea” of a black history trail.

Bullard estimated it would cost more than $100,000 to purchase a bus, pay for a driver and tour guide and print pamphlets detailing the stops.

He suggested walk-throughs – and bathroom breaks – at the homes of musician Louis Armstrong in Corona and inventor Lewis Latimer in Flushing, which are both museums.

Comrie, a councilman in southeast Queens, said the borough president has “some money to give to groups and programs that would make those types of things [like the trail] happen.”

And Vallone, a councilman in northwest Queens, said the trail is “something I would be very open to taking a look at.”

All four candidates said they would also work with the city to increase the numbers of landmark designations in Queens. No clear Republican contender has yet emerged in the race.

HISTORICAL SITES

Here are the sites of the potential black history trail, with locations from the Queens News’ History in Peril series:

- Malcolm X home: 23-11 97th St.

- Louis Armstrong home: 34-56 107th St.

- West Side Tennis Stadium: 69th Ave. and Dartmouth St.

- Lewis Latimer home: 34-41 137th St.

- Jackie Robinson home: 112-40 177th St.

- W.E.B. Du Bois home: 173-19 113th Ave.

- James Brown home: 175-19 Linden Blvd.

SIDEBAR: Former UN Site Won’t Be Landmarked

A recent survey of potential city landmarks left out the former United Nations headquarters in Queens because its facade had changed too much over the years, a city official said.

As described in last week’s Queens News, the New York City Building – a two-time World’s Fair pavilion and current art museum in Flushing – is undergoing a $47 million renovation and partial restoration to be completed in 2010.

But Lisi de Bourbon, a spokeswoman for the city Landmarks Preservation Commission, said the 1939 limestone-and-glass structure was rejected for landmark status in 2002 and is no longer under consideration.

Seventh Installment: Alley Bowled Over

Published May 27, 2008

As a crowd of 5,000 watched, Woodhaven Lanes in Glendale opened with revolutionary bowling technology on July 29, 1959, initiating a 49-year run in which it hosted Hall of Fame athletes and a nationally broadcast TV game show.

As a crowd of 5,000 watched, Woodhaven Lanes in Glendale opened with revolutionary bowling technology on July 29, 1959, initiating a 49-year run in which it hosted Hall of Fame athletes and a nationally broadcast TV game show.

But the 60-lane alley – which closed May 18 – was never designated by the city Landmarks Preservation Commission, and locals fear a developer will demolish the brick-box mainstay before its legacy can be saved.

“That history is absolutely important,” said Jim Baltz, curator of the International Bowling Museum and Hall of Fame in St. Louis, adding he wants to get Woodhaven Lanes’ memorabilia put on display.

Workers are now removing floorboards and machines from the alley to make the interior “spotless” before handing it over to the landlord at the end of the month, according to a manager.

All that will remain is the shell of the alley, established by boxing promoter and bowling center operator Emil Lence, who also owned the 5,000-seat Eastern Parkway Arena in Brooklyn.

Woodhaven Lanes opened in 1959 with innovative “telescore” screens installed on a dropped part of the ceiling, so they’d blend in when turned off.

“Anyone you talk to who’s been around for a while will remember Woodhaven as being the most modern when it opened,” said veteran bowling writer Chuck Pezzano, 79.

In late 1959, Woodhaven Lanes began hosting the NBC game show “Jackpot Bowling,” which aired on Friday nights.

Pezzano, then a columnist at the Paterson (N.J.) Morning Call, said he was hired to prep the show’s host, famed sportscaster Mel Allen, before each episode.

Bowlers on the show had nine frames to get six strikes in a row. Bowling icon Don Carter had the right stuff on Dec. 18, 1959.

“I think I was the first one to hit six in a row and win the jackpot,” said Carter, 81, of Miami. “It was very exciting.”

Bowling Hall of Famer Bill Bunetta, 88, remembers trying to put on a “good show for the audience” when he appeared on May 27, 1960, said Bunetta biographer Danny Ayers.

The game show ended its 15-episode run at Woodhaven on June 24, 1960, with legends Billy Golembiewski and Andy Varipapa on the lanes.

In Sept. 1960, “Jackpot Bowling” moved to 44-lane Hollywood Legion Lanes in California.

But Woodhaven maintained a presence with bowling aficionados. Among those to bowl there in recent years was Kelly Kulick, who in 2006 became the first woman to qualify for the Professional Bowlers Association tour.

“You hate to see something of your pastime torn down,” said Kulick, 31. “I’m sad to see it closing.”

SIDEBAR: ‘Historic’ Race to Fill Councilman’s Seat

Four candidates vying to replace ex-City Councilman Dennis Gallagher pledged support for historic districts in Richmond Hill and Ridgewood during a unique debate last week that focused on preservation in Queens.

The contenders also listed historic sites they’d help landmark if they win the June 3 special election to take over for Gallagher (R-Middle Village), who resigned in April after pleading guilty to sexual abuse charges.

Democrat Elizabeth Crowley singled out Transfiguration Catholic Church in Maspeth and the Woodhaven Post Office among sites she’d help landmark, preventing developers from altering or demolishing them without city approval.

“The list could be endless,” Crowley said, proposing signs at the landmarked spots to detail their history.

Republican Anthony Como heralded his bid to save Woodhaven Lanes, a Glendale bowling alley open since 1959 that was recently shuttered, and proposed yearly public forums on potential landmarks.

Democrat Charles Ober and Republican Tom Ognibene said they would reach out to local history experts to determine which sites need saving.

One of the debate’s more memorable moments occurred when moderator Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council, asked if the candidates would help restore $300,000 for landmarking in the city budget.

Como and Ober vowed they would. Crowley went a step further, saying she’d look for funds from wealthy donors who typically don’t view Queens as a historic area.

Ognibene, however, said he would only support increasing the budget of the city Landmarks Preservation Commission if its members promised to focus more on Queens sites.

“If they tell us they don’t know if they can do it, they can only save buildings in Manhattan, I won’t. That’s the only leverage we have,” Ognibene said.

Ober was the only candidate who vowed to hire a zoning and historic preservation expert to his Council staff.

Under city law, the June 3 special election will decide who holds Gallagher’s seat only through the end of the year.

In November, voters will cast ballots for someone to hold the seat starting in 2009. And in the fall of 2009, voters will pick someone for the seat’s normal four-year cycle.

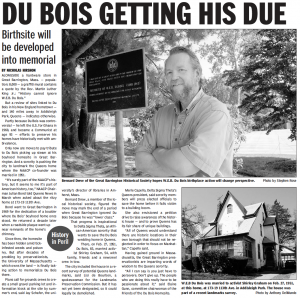

Eighth Installment: Du Bois Getting His Due

Published June 17, 2008

Alongside a hardware store in Great Barrington, Mass. – population: 8,000 – a graffiti mural contains a quote by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.: “History cannot ignore W.E.B. Du Bois.”

Alongside a hardware store in Great Barrington, Mass. – population: 8,000 – a graffiti mural contains a quote by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.: “History cannot ignore W.E.B. Du Bois.”

But a review of sites linked to Du Bois in his New England hometown – and 140 miles away in Addisleigh Park, Queens – indicates otherwise.

Partly because Du Bois was controversial – he left the U.S. for Ghana in 1960, and became a Communist at age 93 – efforts to preserve his homes have historically met with ambivalence.

Only now are moves to pay tribute to Du Bois picking up steam at his boyhood homesite in Great Barrington. And a sorority is pushing the city to landmark the Queens home where the NAACP co-founder was married in 1951.

“It’s surely part of the NAACP’s history, but it seems to me it’s part of American history, too,” NAACP Chairman Julian Bond told Queens News in March when asked about the ritzy home at 173-19 113th Ave.

Bond went to Great Barrington in 1969 for the dedication of a boulder where Du Bois’ boyhood home once stood. He returned a decade later when a roadside plaque went up near remnants of the home’s chimney.

Since then, the homesite has been hidden amid tick-infested weeds and poison ivy. But after decades of prodding by preservationists, the University of Massachusetts – which owns the land – is finally taking action to memorialize Du Bois there.

Plans call for grounds crews to create a small gravel parking lot and information kiosk at the site by summer’s end, said Jay Schafer, the university’s director of libraries in Amherst, Mass.

Bernard Drew, a member of the local historical society, figured the move may mark the end of a period when Great Barrington ignored Du Bois because he was “lower class.”

That progress is inspirational to Delta Sigma Theta, an African-American sorority that wants to save the Du Bois wedding home in Queens.

There, on Feb. 27, 1951, Du Bois, 83, married activist Shirley Graham, 54, with family, friends and a newsreel crew in tow.

The city included the house in a recent survey of potential Queens landmarks, said Lisi de Bourbon, a spokeswoman for the Landmarks Preservation Commission. But it has not yet been designated, so it could legally be demolished.

Merle Capello, Delta Sigma Theta’s Queens president, said sorority members will press elected officials to save the home before it falls victim to a building boom.

She also envisioned a petition drive to raise awareness of the historic house – and to prove Queens has its fair share of unique buildings.

“All of Queens would understand there are historic locations in their own borough that should not be neglected in order to focus on Manhattan,” Capello said.

Having gained ground in Massachusetts, the Great Barrington preservationists are imparting words of wisdom to the Queens sorority.

“All I can say is you just have to persevere. Don’t give up. The people who are doing this really have to be passionate about it,” said Elaine Gunn, committee chairwoman of the Friends of the Du Bois Homesite.

SIDEBAR: Library Offers Up Rare Wedding Invite

A Massachusetts library that owns an invitation to W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1951 wedding is offering to send it to Queens to help landmark the home where the ceremony was held.

A Massachusetts library that owns an invitation to W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1951 wedding is offering to send it to Queens to help landmark the home where the ceremony was held.

Randy Weinstein, founder of the Du Bois Center in Great Barrington, Mass., figured a display of the note – handwritten by Du Bois’ wife, Shirley Graham – might aid a push to save the posh Addisleigh Park house.

“That’s what the mission of the center is – to share,” said Weinstein, adding he’s “up for almost everything” that will achieve landmark status for the home, at 173-19 113th Ave.

The two-page penciled invite – sent by Graham to black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier – asks him to “stay over after the dinner, and be with us for our marriage” on Feb. 27, 1951.

Graham wrote that invitations were sent to “only our immediate families and a few cherished friends.”

Weinstein said he’d give the historic papers to the Queens chapter of Delta Sigma Theta, an African-American sorority that is urging elected officials to save the Du Bois home from destruction.

“That would be very helpful,” said Merle Capello, the sorority’s president in Queens.

She proposed using the invitation as part of a photo op to gain momentum for landmarking.

Delta Sigma Theta began its campaign after reading a Queens News profile of the Du Bois wedding home in March.

Ninth Installment: Hopes Pinned on Landmark

Published June 24, 2008

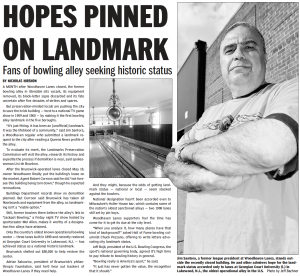

A month after Woodhaven Lanes closed, the former bowling alley in Glendale sits vacant, its equipment removed, its block-letter signs discarded and its fate uncertain after five decades of strikes and spares.

A month after Woodhaven Lanes closed, the former bowling alley in Glendale sits vacant, its equipment removed, its block-letter signs discarded and its fate uncertain after five decades of strikes and spares.

But preservation-minded locals are pushing the city to save the brick building – host to a national TV game show in 1959 and 1960 – by making it the first bowling alley landmark in the five boroughs.

“It’s just fitting. It has been an [unofficial] landmark. It was the lifeblood of a community,” said Jim Santora, a Woodhaven regular who submitted a landmark request to the city after reading a Queens News profile of the alley.

To evaluate its merit, the Landmarks Preservation Commission will visit the alley, research its history and expedite the process if demolition is near, said spokeswoman Lisi de Bourbon.

After the Brunswick-operated lanes closed May 18, owner Woodhaven Realty put the building’s lease on the market. Agent Robert Corroon said he did “not foresee this building being torn down,” though he expected renovations.

Buildings Department records show no demolition planned. But Corroon said Brunswick has taken all floorboards and equipment from the alley, so landmarking isn’t a “viable option.”

Still, former bowlers there believe the alley’s link to “Jackpot Bowling,” a Friday night TV show hosted by sportscaster Mel Allen, makes it worthy of a designation few alleys have attained.

Only the country’s oldest known operational bowling center – three lanes built in 1899 and recently restored at Georgian Court University in Lakewood, N.J. – has achieved status as a national historic landmark.

Brunswick shelled out $50,000 to help restore the center. Adrian Sakowicz, president of Brunswick’s philanthropic foundation, said he’d hear out backers of Woodhaven Lanes if they need help.

And they might, because the odds of getting landmark status – national or local – seem stacked against the bowlers.

National designation hasn’t been accorded even to Milwaukee’s Holler House bar, which contains some of the nation’s oldest sanctioned alleys – two 1908 lanes still set by pin boys.

Woodhaven Lanes supporters feel the time has come for it to get its due at the city level.

“When you analyze it, how many places have that kind of background?” asked Hall of Fame bowling columnist Chuck Pezzano, offering to write letters advocating city landmark status.

Jeff Bojé, president of the U.S. Bowling Congress, the sport’s national governing body, agreed it’s high time to pay tribute to bowling history in general.

“Bowling really is America’s sport,” he said. “It just has never gotten the value, the recognition that it should.”

SIDEBAR: Bowling Hall of Fame Eager for Woodhaven Mementos

Even if bowlers lose their bid to landmark Woodhaven Lanes, the memory of the 60-lane Queens alley may live on – at the sport’s highest institution in St. Louis.

Even if bowlers lose their bid to landmark Woodhaven Lanes, the memory of the 60-lane Queens alley may live on – at the sport’s highest institution in St. Louis.

The International Bowling Museum and Hall of Fame – eager to add memorabilia from the Glendale alley to its archive – has its pick of photos, trophies and other items to choose from.

Woodhaven Realty, which owns the brick-box building that housed the alley for 49 years, proposed sending a 1950s brochure with shots of Woodhaven Lanes to the Hall of Fame.

“It’s the right thing to do,” said Woodhaven Realty agent Robert Corroon. “We’re really happy to send it to them.”

Others also stepped forward with mementos for the hall.

Linda Raia, 47, who began bowling at Woodhaven when she was a kid, said she would part with a patch-laden, royal blue bowling shirt and trophies that date to the early 1970s.

She also snapped photos in the weeks before the alley closed – and swiped two bowling pins after Woodhaven shut its doors May 18.

No items have yet surfaced from the popular NBC game show “Jackpot Bowling,” which aired live from Woodhaven Lanes from December 1959 through June 1960.

But veteran bowling writer Chuck Pezzano – who used to prep “Jackpot Bowling” host Mel Allen – promised to sift through his Clifton, N.J., home for memorabilia, including a script with Allen’s scribbled notes.