In July 2009, Nicholas Hirshon wrote a two-part series for the New York Daily News on the effects of the draconian Rockefeller drug laws.

First Installment

Published July 7, 2009

Three rocks of crack forever changed John Buckmon’s life.

Three rocks of crack forever changed John Buckmon’s life.

A dealer at age 22, Buckmon was lounging by a sketchy Brooklyn apartment building in 1988 when police busted him for selling a gram of cocaine for $60 to undercover cops hours earlier.

Looking back, Buckmon, now 43, wishes he had been sent to a rehab center – like Samaritan Village in Jamaica, where he has lived since October – to conquer his addiction and learn job skills.

But that wasn’t to be under the stiff Rockefeller drug laws – enacted in 1973 to stanch a drug epidemic. The controversial laws were relaxed significantly this spring.

With the change, and a new focus on rehab programs, it’s possible that drug offenders now will have a shot at recovery – and to live well-adjusted lives in society.

But the Rockefeller laws have left their mark permanently on people who lived through them, including Buckmon, who is the first to admit he’s no angel.

Stringent state penalties required minimum prison terms for even the pettiest of pushers like Buckmon, who had sold a scant amount of drugs.

Unaware the rules were that strict, he rejected an offer of 1 1/2 to 3 years in prison – a sweetheart deal considering the harsh laws – because he believed he hadn’t sold enough to justify any prison time.

Buckmon soon recognized his gaffe. The district attorney upped the term to three to six years.

Buckmon took the three years in lockup, learning what he called “useless trades” that never earned him a job.

Had the legislation allowed for rehab, Buckmon believes he would have set himself straight and would now be living with his fiancée, Denise, and three children, ages 6 months to 7 years, in Wyandanch, L.I.

Instead, the Rockefeller laws put him through a “revolving door,” he said, leading in and out of prison for some two decades.

“I always thought it was more of a hindrance than a help,” Buckmon said of his prison time. He then added wistfully, “I might have been anybody in life.”

Now, his crimes are so numerous that he has forgotten many.

Working with limited databases, prosecutors in Brooklyn, Queens and Suffolk County – where Buckmon recalled being nabbed – confirmed eight arrests from 1985 through 2008.

But Buckmon, who used at least 10 aliases, according to state and local records, estimated he has been arrested 100 times and logged 17 years in prison.

Born in seedy East New York in 1966, Buckmon grew up largely with his mom and grandparents while his dad served in the Air Force.

He strayed when his dad returned in the late 1970s and the clan moved to Rochdale. Confused by his father’s belated return to his life, he said he began experimenting with pot as a kid and cocaine in his teens.

Buckmon said he notched his first arrest in 1979 after helping pals rob a kid’s wallet in Bayside, earning one year of probation.

That began a series of misdeeds in the early 1980s, including fights, a burglary and an armed robbery that totaled more probation and a few years in the slammer.

Once released, Buckmon started working for a dealer in Rochdale, eventually getting a beeper and dealing on his own.

That culminated in his 1985 arrest and 3-year term. He tried to stay clean after getting out but his rap sheet scared away potential employers.

“Once I got that arrest for drugs, that’s when it started showing up on my record,” he said, arguing his extended Rockefeller sentence – and subsequent gap on his resume – hindered his job search.

After an arrest for possessing cocaine and pot in February 2008, Buckmon jumped at an opportunity to enter rehab. He eventually came to Samaritan Village, where he must stay for 18 to 24 months under counselors’ watch.

Added Buckmon, “I’m glad I’m here. I’m learning so much about myself and the things that kept me out there for so long.”

SIDEBAR: Birth of the Rockefeller Drug Laws

The original incarnation of the Rockefeller drug laws, envisioned by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller and passed in May 1973, was so harsh that even his close advisers bemoaned how it would lock up minor offenders and overwhelm jails.

Rockefeller wasn’t swayed. Troubled by the state’s drug epidemic, he had asked the chairman of a rehab program to go on a fact-finding mission in 1972 to Japan, which had the lowest addiction rate of any major nation.

The chairman credited Japan’s successful war against drugs to life sentences for sellers, said Rockefeller aide and biographer Joseph Persico.

The governor first mentioned the idea to his staff in the basement of his Westchester County mansion, Kykuit, in the fall of 1972. “On drugs, anyone who pushes gets life in prison,” Rockefeller said, according to Persico. “And I mean life – no matter what amount. No more of this plea bargaining, parole and probation.”

Ignoring a liberal counteroffensive, Rockefeller championed iron-fisted laws that forced judges to impose fixed minimum sentences to drug criminals, regardless of mitigating factors.

On top drug charges, the laws forbade pleas, parole, probation and suspended sentences.

Anyone charged with possession or sale of 4 ounces or more of cocaine or heroin faced a minimum of 15 years to life in prison, said attorney Jon Wool of the Vera Institute of Justice.

First-time offenders who sold less than 2 ounces had to serve at least one year to life. In the late 1970s, such crimes were dropped to a lower felony that carried a one- to three-year minimum.

In 2004, legislators eased the laws by doubling weight thresholds and lowering minimum sentences for top drug charges. And this spring, the state eliminated mandatory minimum prison terms on drug sales of less than 4 ounces for those with no prior convictions. Judges can sentence those offenders to probation with drug treatment.

Second Installment

Published July 14, 2009

About a month and 20 interviews into his job search, former drug dealer John Buckmon – once sentenced under the stiff Rockefeller drug laws and now finally getting an opportunity at rehab – was feeling hopeless and inadequate.

About a month and 20 interviews into his job search, former drug dealer John Buckmon – once sentenced under the stiff Rockefeller drug laws and now finally getting an opportunity at rehab – was feeling hopeless and inadequate.

“It’s kinda hard out there,” he said in June to his counselor at Samaritan Village, a substance abuse treatment center in Jamaica. “In the back of my mind, I feel like I don’t have a chance.”

Buckmon, 43, who estimates he has been arrested 100 times and logged 17 years in prison, faces two key obstacles due to the harsh laws that he feels kept leading him to the slammer when he really needed treatment.

First, he must persuade prospective employers to look past his extensive rap sheet – littered with drug possessions and sales dating back to the mid-1980s – and subsequent résumé gaps.

Second, he has to overcome poor self-esteem stemming from alcohol and cocaine addictions that went untreated through his prison terms and that sometimes left him feeling like a failure.

They are roadblocks that haunt even minor drug criminals nabbed under the state’s 1973 Rockefeller rules – eased this spring to reduce sentences, offer rehab and allow judges to seal records for some offenders.

Certain nonviolent offenders can have their records sealed even if they were convicted long before the recent relaxing of the laws, as long as they have completed sentences and treatment.

But that doesn’t cover Buckmon – who began experimenting with drugs as a teen in Rochdale – since he has committed too many crimes, including burglary and armed robbery.

With an unsealed record, Buckmon is re-entering the workforce with the support of Samaritan Village, where he meets twice a week with vocational rehab counselor Nelly Lopez.

Queens News sat in on one of those sessions in June. When Buckmon told Lopez then that he feels hopeless at times, she offered comforting words.

“It’s normal to be scared,” she assured him in a soft, calm voice. “It’s normal to see a lot of people, especially now, applying for the same job. Somehow, somewhere, somebody’s going to hire you.”

Her faith rubbed off on him. “It kinda inspires me, because now I know I’m not the only one,” Buckmon said. “It is a recession, and everyone is affected by it.”

Buckmon also attends twice-a-month group sessions at which instructors show videos on how to find jobs, then answer questions.

At last count on Friday, Buckmon had gone to about 30 job interviews. Between lockup stints, he has worked as everything from a barber to a security guard – a job he eventually lost because he didn’t tell his employer about his criminal history.

Among his most attractive qualifications is a commercial driver’s license from North Carolina – where he lived in 2004 – that he hopes to switch to New York.

He has already met with reps from several paratransit and school bus companies, as well as corporations that operate delivery trucks, including Frito-Lay and Manhattan Beer.

Samaritan Village’s program director, Laurie Lieberman, applauded Buckmon’s tenacity.

“He doesn’t fit the stigma,” she said. “He’s very concerned about not being a negative role model. He’s willing to go through that transformation.”

Beyond securing employment, Buckmon plans to embrace a role he already has – being a father.

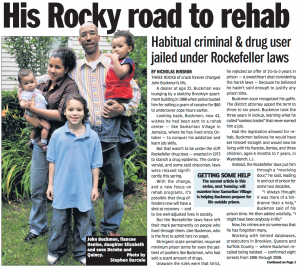

On a rare day off from job-hunting recently, Buckmon was allowed to visit his 23-year-old fiancée, Denise Roman, and three children, ages 6 months to 7 years, in Wyandanch, L.I.

“He’s changed a lot,” Roman said as the family’s brown-and-white cocker spaniel, Cuddles, scurried across the living room. “He’s not into drugs no more. He’s more into the family.”

Buckmon gently bounced his infant daughter Elizabeth on his lap while describing how Samaritan Village has helped him turn a corner in life.

“Now,” he said, “I don’t need to go out on the streets.”

SIDEBAR: Albany Leaders Spar Over Reforms

Before a Republican-led coup tossed the state Senate into chaos, Albany leaders were sparring over a new guideline that lets judges seal records of some rehabilitated drug felons to prospective employers.

Passed amid sweeping changes to the stiff Rockefeller drug laws this spring, the provision allows courts to prohibit rap sheet releases for certain non-violent drug offenders who complete sentences and treatment.

Access is still granted to law enforcement officials, agencies that issue gun licenses and honchos who hire police or peace officers. Papers would be unsealed if criminals are arrested again.

Previously, records could be sealed only with permission from a prosecutor.

“The goal is to provide every possible protection for public safety while allowing people who have successfully completed drug treatment to get a job,” said Sen. Eric Schneiderman (D-Manhattan), who crafted the reforms.

But Republicans, led by Sen. Frank Padavan (R-Bellerose), are pushing a bill that would repeal the sealing provision.

They contend the current law allows drug criminals to work undetected at nursing homes, day care centers and schools.

“Conceivably, you could have someone become a teacher in a classroom having previously being convicted of selling drugs in a schoolyard,” Padavan warned.

Schneiderman argued Padavan’s bill doesn’t “make much sense,” but insisted he is open to other suggestions.

He pointed to another bill, introduced by Sen. Brian Foley (D-L.I.), that would extend access to drug records to any employer that fingerprints workers, such as educators and caregivers to the elderly and mentally ill.

Advocates for prisoners’ re-entry into the workforce urged patience.

“We’ve finally had a chance to do some meaningful reform,” said Glenn Martin of the Fortune Society. “Let’s give it a chance.”